The different museums on Berlin’s Museum Island often make it difficult to decide which one to visit. The Bode Museum is not only worth a visit from an architectural point of view, the interesting exhibitions with wonderful exhibits particularly captivated me.

History of the museum

Wilhelm Bode, then assistant director of the Royal Museums in Berlin, suggested in 1878/79 the construction of a museum for sculptures, paintings and decorative arts from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. His favored location was on Museum Island.

With the support of Crown Prince Frederick William, the building site on the northern tip of Museum Island was determined. After the Crown Prince, as Frederick III, took over the government, he appointed Chief Architect Ernst Eberhard Ihne as court architect and commissioned him to build the Renaissance Museum. Frederick III was in power for only 99 days (“99-day emperor”), then he died. Later, the museum was named the Emperor Frederick Museum in his honor.

Bode, by then director of the Gemäldegalerie and the sculpture collection in the Altes Museum, founded a private sponsoring association for the new planned museum, construction funds were approved from the state budget, and the city of Berlin financed the construction of the Monbijou Bridge, which provided access to the museum. Then, after many years of preliminary planning, ground was finally broken in 1898.

Kaiser Friedrich Museum

In 1904, the museum was inaugurated and showed its visitors works of art from the Christian epochs, the Picture Gallery, the Early Christian-Byzantine Collection, the Coin Cabinet and the Islamic Department. Soon the exhibition space was no longer sufficient for the existing and newly added exhibits and Bode made further plans for new museum buildings.

In 1920, Bode had to resign from office at the age of 75. He died only 9 years later and found his final resting place at Berlin’s Luisenfriedhof II in the Westend district.

The museum was closed during the Second World War. The artworks were initially secured in the basement of the building, and ceilings and architectural fixtures were also dismantled. Later, many works of art were moved to the control tower of the Flak Bunker Friedrichshain. Unfortunately, fires destroyed many works of art there. At a later date, many works of art were also brought to safety in salt mines. After the end of the war, American troops transported the art from there to Wiesbaden, the Central Art Collecting Point of the American military government.

In 1943, during air raids on Berlin, the Kaiser Friedrich Museum was also hit, causing damage to parts of the outer facade, roofs and windows.

Development after the Second World War

The museum suffered almost much greater damage after the Second World War. Snow and rain got into the building through the defective roof and attacked the structure. After a while, funds were finally made available for securing measures on the building.

In 1949, plans emerged to demolish the Kaiser Friedrich Museum. The Berlin City Planning Office saw it as an “architecturally worthless monument to imperialism” with restoration costs that were far too high. Fortunately, the general director of the museums was able to prevent this. He could not prevent, however, that the inscription “Kaiser-Wilhelm-Museum” was removed and the museum was now called “Museum am Kupfergraben”. The equestrian monument to Emperor Frederick III, which stood in front of the building, was dismantled and melted down.

A little later, the inscription “Staatliche Museen zu Berlin” was placed on the facade. The restoration of the building progressed slowly. Due to the high costs, the domes could not be covered with copper, but were given a slate roof.

In 1956, the museum is renamed the “Bode Museum”.

For the 750th anniversary of Berlin (1987), the Bode Museum was once again in its former glory. The large domed hall shone in bright light, the Kameke Hall and the Basilica had been redesigned, the statues of the Prussian generals and Pigalle’s sculptures were once again in the small dome, and the restored Gobelin Hall was accessible.

Until the fall of communism in 1990, it was possible to visit the Egyptian Museum with the Papyrus Collection, the Museum of Prehistory and Early History and the Coin Collection.

With reunification in 1990, Berlin’s museum landscape also had to restructure and unify. The process was not easy and took some time. Finally, it was agreed that the Bode Museum would house the Numismatic Collection and the Early Christian-Byzantine Collection. In addition, extensive renovation measures were to be carried out according to historical specifications.

In 2004, on the occasion of the centenary of the Bode Museum, the Numismatic Collection was the first to open. At the end of 2005, the general renovation was completed and the exhibitions could move into the newly designed rooms.

Visit to the Bode Museum

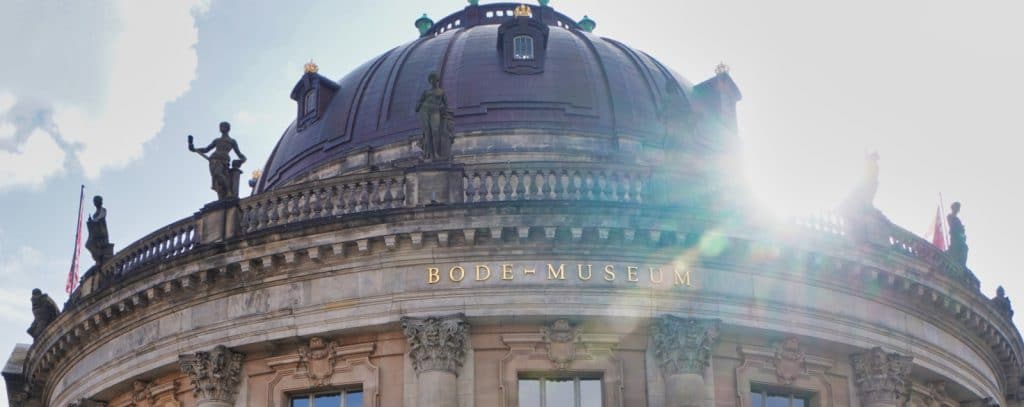

From S-Bahn station I walk through a small park over the Monbijou Bridge to the Bode Museum. What an impressive building on the top of the Museum Island stands there. A large dome, it is almost 40 meters high, rises in front of me. The copper roof shines and above the entrance to the museum I discover the lettering Bode Museum. The neo-baroque building made of sandstone already inspires me from the outside.

But it really takes my breath away when I step into the entrance hall. I stand in the domed hall and don’t know where to look first: at the pompous dome, at the gilded banisters or at the huge equestrian statue of the Great Elector in the center of the hall.

The stairs run in a harmonious curved line to the upper floor. It reminds me a bit of a palace staircase leading to the stately rooms. I also find the dome design beautiful, it almost seems like in a cathedral or cathedral.

Next, I enter a hall from which one can access exhibition rooms adjacent to the side. At the end of the hall, one reaches the Small Dome Hall with a staircase.

On the upper floor there are marble statues of the six generals of Frederick the Great. Here, too, there are several doors leading to different exhibition areas.

Admittedly, I strolled quite aimlessly through the exhibition rooms, some of which were very impressive, lingering here and there to take a closer look at individual pieces.

Coin Cabinet in the Bode Museum

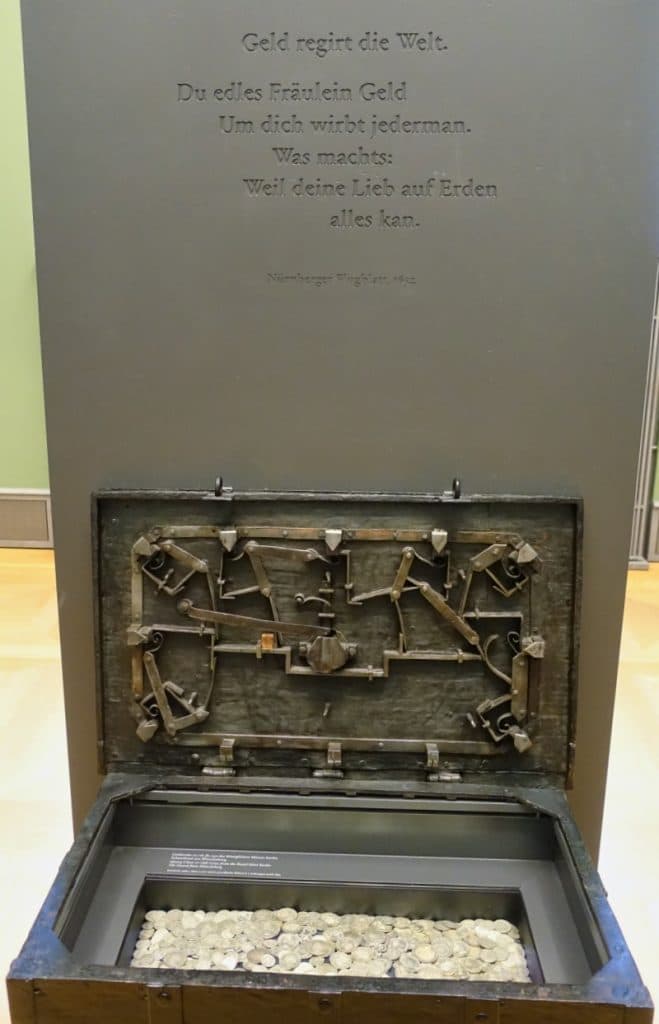

The Numismatic Collection is a special collection of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and is one of the largest numismatic collections in the world.

It all began in the late 16th century with a collection of the Kunstkammer of Brandenburg electors. In 1868, the collection then received the status of its own museum.

The special thing about the collection is that there are many complete coin series from the beginning of coinage in the seventh century B.C. in Asia Minor to the present. This involves more than 500,000 coins, but not all of them are shown.

In the Bode Museum there are four exhibition rooms divided into smaller coin cabinets, where about 4000 coins and medals are displayed. For lovers of this subject, a real paradise. From very small to large unwieldy coins, there is a lot to discover in the numerous showcases. I find it very exciting to see how the shape of the coins is becoming more and more similar to today’s coins.

In the basement of the museum there is a large vault where most of the collection is stored. I read that by appointment you can probably also see these coins there.

Sculpture collection

The beginnings of the sculpture collection date back to the early 17th century. At that time, the foundation of a collection of sculptures from the Italian Renaissance was laid in the Brandenburg-Prussian Kunstkammer in the Berlin City Palace.

Over time, the collection of exhibits grew and Wilhelm Bode finally presented them to the public as a sculpture collection. He attached great importance to presenting them in combination with paintings, pictures and furniture. Even today, one walks through the sculpture collection and discovers paintings and furniture or marvels at imposing fireplaces.

Despite numerous losses due to the Second World War, the sculpture collection is now one of the world’s largest collections of older sculpture.

During a tour of the sculpture collection, one can admire exhibits from the Middle Ages to the late 18th century. In addition to works from German-speaking countries, many beautiful exhibits from Italy are also on display. Especially works from the Italian early Renaissance, which are a main focus of the exhibition, by famous artists such as Donatello are the attraction of many visitors. Another focus of the sculptures on display are the late Gothic works by German artists.

During my tour, I kept stopping enthusiastically in front of individual works of art. What beautiful and often so detailed works I discovered in the different eras and by the most diverse artists.

James Simon Gallery

During my tour, I also stopped by the James Simon Gallery.

James Simon (1851-1932) was not only a successful entrepreneur, but also a patron of Berlin museums. He donated his collection of almost 500 works of the Italian Renaissance on the condition that they be exhibited in a room in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum for 100 years.

Unfortunately, his Jewish ancestry did not permit this during the National Socialist era and the cabinet was dissolved in 1939. Now this room has been reinstalled in its original place.

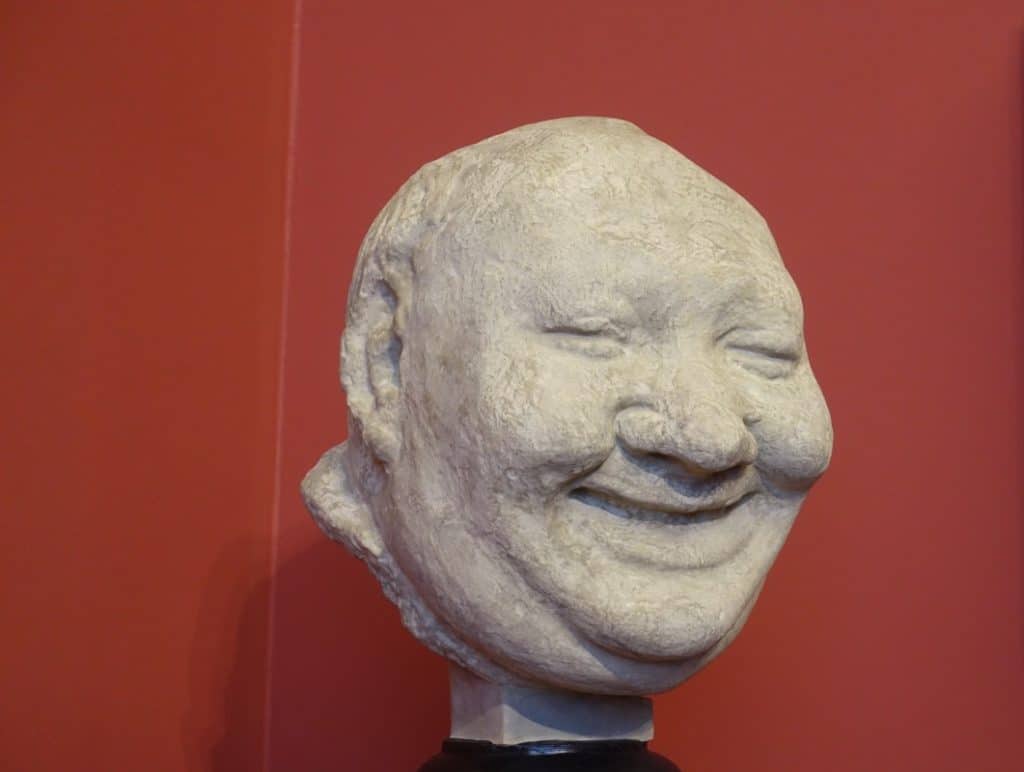

On display is a room with a large round table from the 16th century and some other furniture placed on the walls. Small bronze figures, statues and paintings are shown. In the corner of the room I discover the head of a man – isn’t he smiling beautifully, kindly and friendly.

Merseburg hall of mirrors

Astonished, I stop in another room. This is the Merseburg Mirror Cabinet.

Duke Wilhelm of Saxe-Merseburg had this beautiful room design built for an apartment in Merseburg Castle in 1712/15. Later it was brought to the court in Dresden. The damage of the Second World War was restored very lavishly from 1998-2005. Why it was not built in Merseburg Castle is unknown to me.

The interplay of the mirroring and gilded carvings is particularly interesting. If you look into the mirrors at certain angles, you have the feeling that there is an infinite repetition of the image.

For a long time it was assumed that porcelain was presented in the mirror cabinet. Today it is known that it was an art chamber where goldsmith’s work, ivory, amber and other valuable objects were collected.

Museum of Byzantine Art

In some rooms of the Bode Museum there is the Museum of Byzantine Art. Here is shown a collection of works of art and everyday objects from the 3rd – 15th centuries. The works come from the Byzantine Empire, which at that time stretched across the Mediterranean, North Africa, the Middle East and Russia.

Thus, in addition to late antique sarcophagi from Rome, figurative sculptures from the Eastern Roman Empire, ivory carvings from Byzantine court art and everyday objects from Egypt are also on display.

During my tour, I visited this part of the extensive exhibition rooms in the museum at the very end. I was particularly impressed by the wonderful mosaic that I discovered there.

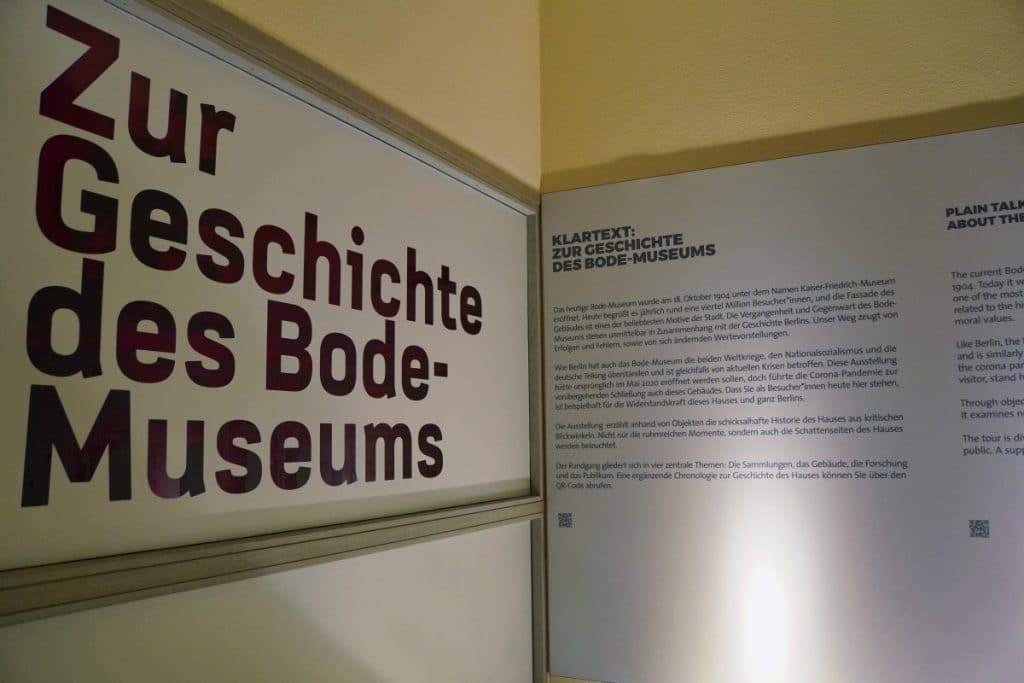

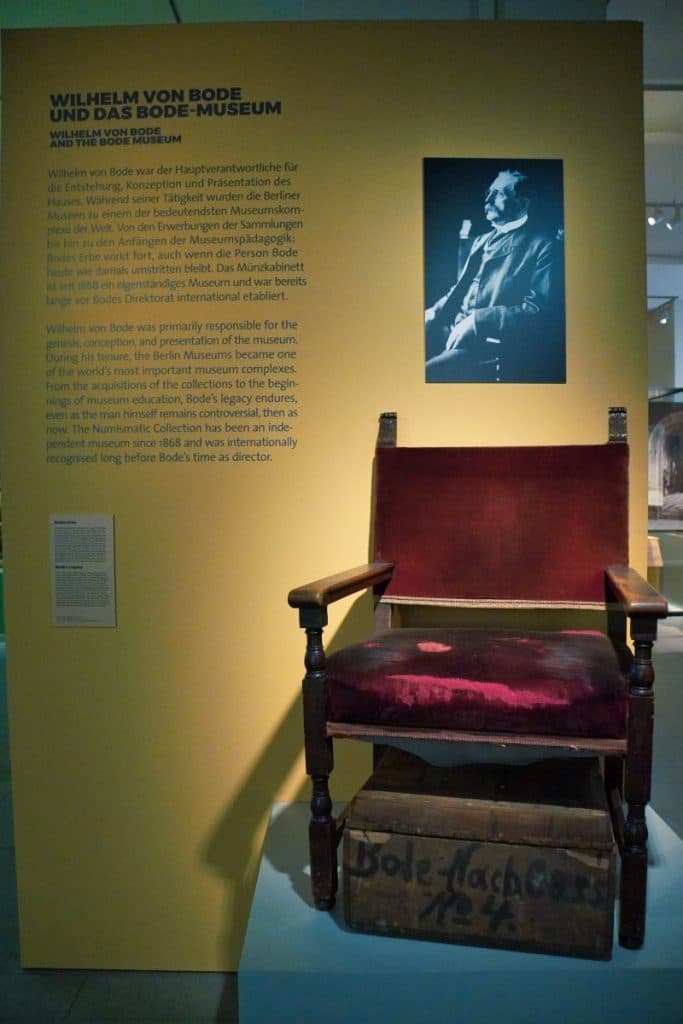

Exhibition: Klartext – On the History of the Bode Museum

The temporary exhibition “Klartext – Zur Geschichte des Bode-Museums” is located somewhat hidden in the basement of the museum.

Four well-organized sections report on the museum’s collections, building, research and visitors. Here I learned a lot about the history of the Berlin museum. Facts that are otherwise rather in the background during a museum visit, but always interest me very much. Exhibitions are interchangeable in a building, but a building itself is not. It tells so much about life in a country / city, which is forgotten far too quickly.

I also find it exciting that research and related restoration measures on exhibits are reported here. When you visit a museum, you often don’t realize how much work often goes into a piece of a collection before it is shown to visitors.

Visitor entrance

Am Kupfergraben, at Monbijoubrücke

10117 Berlin

Opening hours

Tuesday – Sunday: 10 – 18 h

Monday: closed

Admission fees:

Adults: 12,-€

Discounts are offered.

The visit to the Bode Museum and the permission to use the photos was kindly supported by the National Museums in Berlin.

Leave a Reply